For the First Time in 232 Years, a Black Prosecutor Leads a Storied Office

Damian Williams, an unassuming figure with stellar credentials, is now the most powerful federal law enforcement official in Manhattan.

Damian Williams the day after his confirmation as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York.

Todd Heisler/The New York Times

By Benjamin Weiser

Oct. 7, 2021

One night in December 2018, two dozen lawyers and judges gathered at a fashionable restaurant in New York’s TriBeCa neighborhood to welcome a new member, Damian Williams, into their distinguished fold.

Each had once been a federal prosecutor in Manhattan, running a special unit in the U. S. attorney’s office that investigated fraud on Wall Street. It was a job barely known to the public. But among New York’s corporate and legal elite, it was a position of power and influence, often shared by co-chiefs.

Mr. Williams was the latest appointee. That night, amid jocular toasts and ribbing, Judge Jed S. Rakoff read a whimsical poem in honor of Mr. Williams, gently mocking his self-effacing nature with an out-of-character boast:

“I’m now co-chief — my name is Damian,” the judge began. “Things will never be the same again.”

The judge was only teasing, but in one sense he got it right.

On Tuesday, Mr. Williams, 41, was confirmed by the Senate to be the next United States attorney for the Southern District of New York — a position whose occupants have included future judges, senators, cabinet members and a New York City mayor. The appointment would make Mr. Williams the most powerful federal law enforcement official in Manhattan and, significantly, the first Black person to lead the storied 232-year-old office.

The Southern District handles some of the nation’s most complex fraud, terrorism and corruption cases, including prosecutions that reached former President Donald J. Trump’s inner circle. The office is preparing to try Ghislaine Maxwell, the longtime companion to Jeffrey Epstein, on sex-trafficking charges (she has pleaded not guilty), and it is investigating Rudolph W. Giuliani, the former New York City mayor, Trump lawyer and onetime Southern District U.S. attorney, over his dealings in Ukraine before the 2020 presidential election. He has denied wrongdoing.

Mr. Williams assumes the Southern District’s leadership roughly 16 months after the murder of George Floyd by a Minnesota police officer and the ensuing mass protests calling for an end to racism in the criminal justice system.

“Beyond his extraordinary qualifications, Damian is the right person at this time in history to be the U.S. attorney for Manhattan,” said Theodore V. Wells Jr., a Black partner at the law firm Paul, Weiss and one of the nation’s most prominent litigators.

“It’s important for both Blacks and whites to see a person of African-American descent — especially in this time where there’s so much social unrest — in that top job,” Mr. Wells said.

David E. Patton, the city’s federal public defender, said Mr. Williams now has the opportunity to institute key reforms in the way his prosecutors charge cases, like embracing President Biden’s campaign pledge to end mandatory minimum sentences.

“This is a core issue he can tackle,” Mr. Patton said.

Another issue Mr. Williams will confront is diversity in his office: Of its 232 assistant U.S. attorneys and executives, only seven — including himself — are African American.

Mr. Williams’s ascent follows several years of tumult in the office, which has long guarded its independence from Washington, earning it the nickname the Sovereign District.

Two of the previous four top Southern District prosecutors were fired by the Trump administration, most recently last year when the office was rocked by the dismissal of Geoffrey S. Berman after Attorney General William P. Barr tried unsuccessfully to replace him with a political ally. The New York Times has also reported that Mr. Barr and other Justice Department officials tried to interfere with some of the office’s key cases and investigations.

Mr. Williams declined to comment for this article, which is based on interviews with more than two dozen of his former colleagues, defense lawyers and others who have known him for years.

“I think he really enjoys the work that he is doing at the U.S. attorney’s office,” said Addisu Demissie, a political strategist who met Mr. Williams in 2003 when both men worked in Iowa as field organizers on Senator John Kerry’s Democratic presidential campaign. “The feeling that you go to work every day and are on the side of good is something that for him is a driving force in his happiness, in his professional career.”

Another close friend, the actress Natalie Portman, who has known Mr. Williams since they were Harvard students two decades ago volunteering for an arts organization that mentored children, said his career path was no surprise.

“There was always a sense that he wanted to go into public service,” Ms. Portman said.

But while his appointment to one of the most prominent seats in the legal world appeared to be the logical next step in a remarkable career, Mr. Williams’s path was neither simple nor easy. To excel professionally, those who know him best said, he had to overcome his family’s pain and loss, including the arrest of his father, a doctor in Georgia, on a Medicaid fraud charge.

Over the Southern District’s long history, its alumni have gone on to serve on the Supreme Court, as U.S. attorney general, secretaries of war and homeland security, F.B.I. director, police commissioner, Manhattan district attorney and New York City mayor (Mr. Giuliani). Yet another, who served in the 1880s, later won the Nobel Peace Prize.

But the office has never been led by a Black person.

“It’s not just that Damian is going to be a Black U.S. attorney,” said Martin S. Bell, a former Southern District prosecutor who is also Black. “He’s also somebody who offers a heightened potential for thoughtfulness and creativity when it comes to bigger questions concerning criminal justice — and the office’s own ability to be credible to a rich, vast and diverse constituency of New Yorkers.”

Mr. Williams was born in Brooklyn, but he was raised in the Atlanta area, where his family moved when he was an infant. His parents, immigrants from Jamaica in the early 1970s, met as students at Howard University in Washington, where his father studied medicine and his mother nursing.

He attended a private day school, Woodward Academy, excelling in academics and serving as student body president in his senior high school year.

At Harvard, Mr. Williams majored in economics; at the University of Cambridge, he obtained a master’s degree in international relations.

He joined the Kerry campaign in August 2003, working first in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and later in South Carolina. In the spring of 2004, with law school months away, he was hired by Terry McAuliffe, then chairman of the Democratic National Committee, as his “body man” — his driver, executive assistant and one of his closest aides.

“I threw so much at him,” Mr. McAuliffe said. “Never rattled, always smiling, solid as a rock.”

But late that July, Mr. Williams was shattered when his older sister, Tiffani Simone Williams, 25, to whom he was devoted, died suddenly in Atlanta from an infection after a root canal.

He entered Yale Law School that fall, grieving but finding the strength to rebuild and move forward, his friends and professors recalled.

As a student at Yale Law School in 2006. “He was one of those students who doesn’t speak a lot in class,” one of his professors there said, “but every single person listened to every word he said.”Credit...Joseph Rodriguez

It began a formative period for the future prosecutor, including the summer after his first year at law school, when he worked as an intern in the Southern District.

Harold Hongju Koh, then the law school’s dean, recalled conversations with Mr. Williams about how the criminal justice played out at two levels: in the individual case and the system more broadly.

“The question is how do you do both — get justice in an individual case, and not ending up becoming an instrument of an unjust system?” Professor Koh said. “He was very attuned to that challenge.”

Mr. Williams also took a keen interest in voting and civil rights, said Heather Gerken, a professor who is now Yale Law School’s dean. She said he turned in one paper on the 15th Amendment, which bars discrimination in voting on account of race, that was so insightful it caused her to revise her class notes and rethink how she taught the topic.

“He was one of those students who doesn’t speak a lot in class,” she said, “but every single person listened to every word he said.”

He also published a meticulously researched and reasoned paper in the influential Yale Law Journal. It examined the devastating impact of Hurricane Katrina in displacing Black voters in New Orleans, and it offered an ingenious proposal for how the Justice Department could use a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to protect them from disenfranchisement.

The law journal, in fact, also posed a different kind of challenge for Mr. Williams, drawing on his skills as a mediator and emerging leader. After an earlier set of journal editors invited a speaker to appear at a campus symposium in March 2006, a bitter debate erupted when it was discovered that the speaker once had made racist references in an online posting.

Amid bad feelings about the episode and broader questions about the journal’s dedication to having a range of voices in its writings and among its staff, a new editor in chief, Jessica Bulman-Pozen, named Mr. Williams to a specially created ombudsman position.

“It was just universally understood that Damian would be a person who had the judgment and respect to help set a new path,” she said.

“The real question isn’t how we avoid a situation like this but rather how we adapt going forward,” Mr. Williams told The Yale Daily News then. “The process sometimes matters as much as the outcome.”

After graduation in 2007, Mr. Williams held two prestigious clerkships in Washington, for Merrick B. Garland, then a federal appellate judge (and now the attorney general), and Justice John Paul Stevens on the Supreme Court.

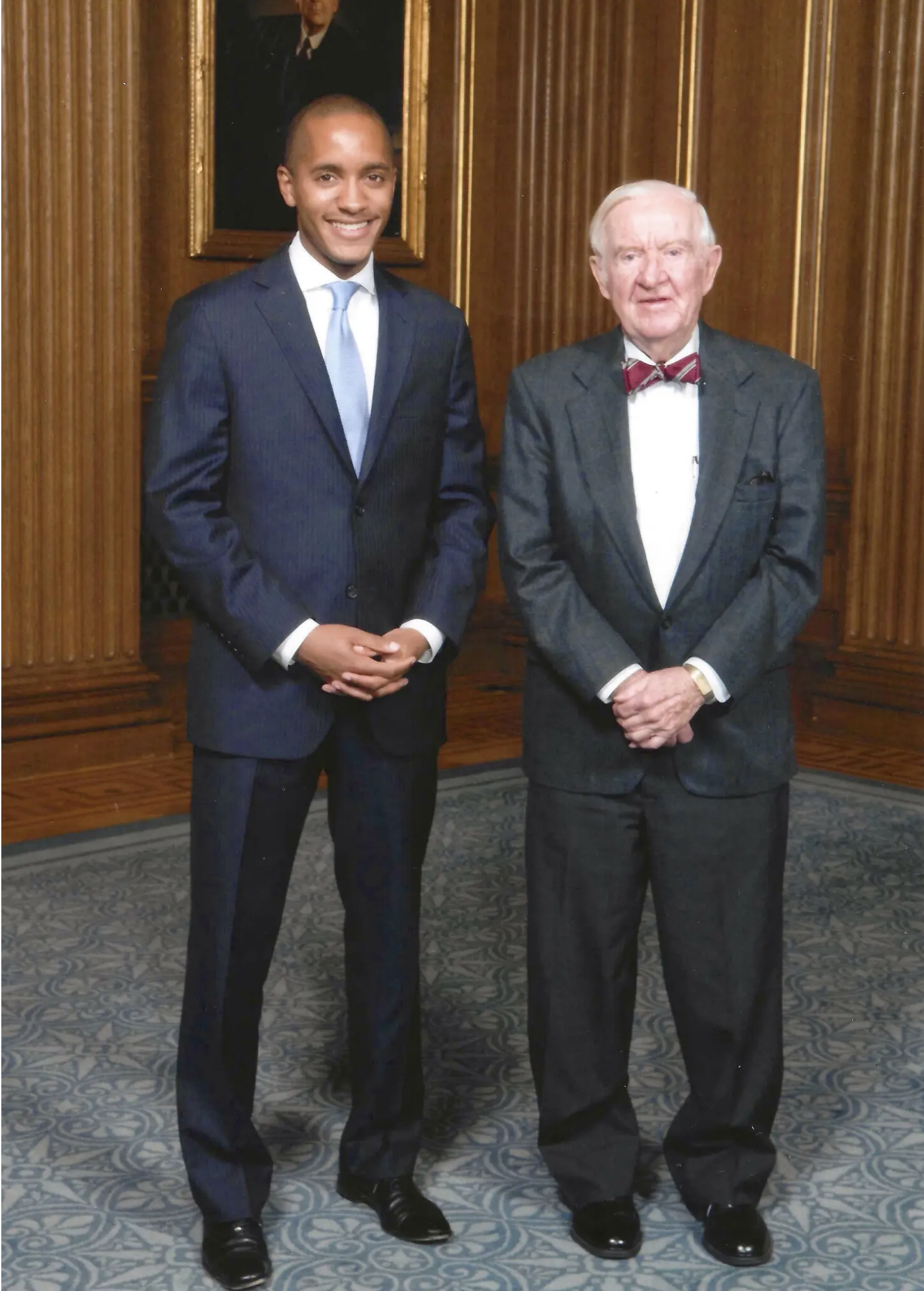

With Justice John Paul Stevens, for whom he was a clerk after graduating from Yale Law.

While clerking for Judge Garland, he also took a fateful ride on a discount bus one night from Washington to New York, and began talking with his seatmate, Jennifer N. Wynn. They were still talking when the bus pulled into the Port Authority near midnight, and they would marry five years later. (Ms. Wynn, a former teacher and director of education at the Obama Foundation, today runs her own consultancy on leadership development and teaches at the Stern School of Business at New York University.)

Mr. Williams then spent three years as a litigation associate at Paul, Weiss, a Manhattan law firm known for its white-collar defense practice. He worked closely with Mr. Wells, one of the leaders of the firm’s litigation department, assisting in his representation of Gov. David A. Paterson of New York in a 2010 state ethics inquiry, and in Mr. Wells’s successful defense of Citigroup in a three-week civil trial.

With his stellar academic and clerkship credentials, Mr. Williams most likely earned a sizable salary and bonus at the firm, but his friends said he lived frugally, avoiding expensive restaurants, for example, with his eye on public service.

“He gave himself a very tight budget,” Ms. Portman said. “He was like, ‘The goal of this is to pay off my debt, and I don’t want to get addicted to the lifestyle.’”

“He had such a focus and a discipline on what he wanted to do,” she added, “that really felt different from anyone else I knew.”

In February 2012, Mr. Williams left private practice to become a prosecutor in the Southern District, then headed by Preet Bharara. “He was a no-brainer hire,” Mr. Bharara recalled.

Among his earliest trials was one involving a drug-related shooting in the Bronx.

Randall W. Jackson, a former prosecutor who assisted in the trial, said he was struck by Mr. Williams’s empathetic approach with several fearful young witnesses.

“Damian had just a natural way of talking to them about what it meant to testify,” Mr. Jackson said, “that I think communicated without him ever having to say it: I’m a person that cares about what happens here and is not going to do anything to hurt you.”

During his first year in the office, Mr. Williams learned of the arrest of his father, Dr. Andre Williams, an obstetrician-gynecologist in the Atlanta area. An indictment filed in DeKalb County Superior Court in December 2012 accused Dr. Williams of accepting Medicaid funds to perform elective abortions. He pleaded guilty in 2014, received probation and was ordered to pay $215,000 in restitution, court records show.

Damian Williams has not spoken publicly about his father’s case. A person close to Mr. Williams, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said it came as a total surprise, that he and his father were not close (his parents are divorced) and that he separated himself completely from his father’s case and had no involvement in his defense.

The experience left Damian upset and disappointed, the person said, but it also deepened what he had long believed: that families and others around those being prosecuted feel the pain of a prosecution even when they have not done anything wrong.

In nearly 10 years as a prosecutor, Mr. Williams has handled trials involving drugs and guns, identity theft, and bank and accounting fraud, and he has been involved in and supervised countless other cases and investigations.

Most prominently, he helped win the convictions of Sheldon Silver, the former powerful Democratic speaker of the New York State Assembly, on corruption charges; and of Chris Collins, the former Republican congressman from western New York, who pleaded guilty in an insider trading case. (He was later pardoned by Mr. Trump.)

Among his colleagues, Mr. Williams was known as an intellectual force but also as unpretentious and quick to laugh at himself. “He was not somebody who wore his résumé on his sleeve,” Rebecca Ricigliano, an early supervisor in the narcotics unit, said.

He would work late at night on complicated legal briefs with Bob Marley playing in the background. He remained endearingly frugal, using an empty pasta sauce jar on his desk as a drinking glass. In meetings, he could seem reserved.

“I think that’s because he is such a good listener,” said Lisa Zornberg, a former prosecutor who ran the office’s criminal division from 2016 to 2018. “He reads people, he reads rooms, he takes it all in.”

But in front of a jury, she said, he was engaging and persuasive.

He also became known as one of the few Southern District prosecutors who appeared before juries without notes, although he drafted his jury presentations in advance and rehearsed them in the office.

The Sheldon Silver corruption case became Mr. Williams’s most high profile trial.

Mr. Silver’s 2015 conviction had been the capstone of a Southern District campaign against Albany’s culture of secrecy and graft, championed by Mr. Bharara and carried out by the Southern District’s public corruption unit.

But in March 2017, Mr. Bharara was fired by the Trump administration, and a few months later, Mr. Silver’s conviction was overturned on appeal after the Supreme Court, in a different case, narrowed the definition of corruption.

Joon H. Kim, who became acting U.S. attorney, announced a retrial, but faced a problem: The original Silver prosecutors had all left the office for other jobs.

The stakes for the retrial were extremely high, recalled a former prosecutor, Tatiana R. Martins, who was then the chief of the corruption unit.

“I was reminded more than once that it was a case we could not lose,” she said.

So, Mr. Kim formed a new team, selecting Ms. Martins and another experienced corruption prosecutor, Daniel C. Richenthal — and adding Mr. Williams, who was prosecuting securities fraud cases. He had no background in the corruption unit, where his selection raised some eyebrows, some former colleagues said.

But Mr. Kim, explaining his rationale, said Mr. Williams was as skilled a trial lawyer as there was in the office.

The prosecutors had only months to master the evidence, prepare witnesses and practice jury presentations.

In May 2018, after a two-week trial, Mr. Silver was convicted, and although several counts were again overturned on appeal, he received a 6½-year prison sentence.

As for Mr. Williams, on the day the trial began, he was the prosecutor who first rose in the packed courtroom and delivered an opening jury address detailing the story of a powerful politician who had become blinded by greed. Mr. Williams’s statement would run 22 pages in the official transcript.

He used no notes.

Alain Delaquérière contributed reporting.

A correction was made on

Oct. 6, 2021

An earlier version of this article misidentified a supervisor who worked with Damian Williams in the narcotics division. She is Rebecca Ricigliano, not Racigliano.

When we learn of a mistake, we acknowledge it with a correction. If you spot an error, please let us know at nytnews@nytimes.com.Learn more

Benjamin Weiser is a reporter covering the Manhattan federal courts. He has long covered criminal justice, both as a beat and investigative reporter. Before joining The Times in 1997, he worked at The Washington Post. More about Benjamin Weiser

A version of this article appears in print on Oct. 10, 2021, Section MB, Page 1 of the New York edition with the headline: He’s a Legal Force, and a First. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe